Summary

This blog post has been written following an NCACE Evidence Café event held in November 2025 on the theme of this blog’s title. It uses data from REF 2021 Impact Case Studies to identify formal collaborations between universities and cultural institutions, discussing the dynamics of how knowledge is produced and what drives transformative collaborations.

It identifies two key modes of knowledge production – traditional knowledge production and context driven knowledge production - and positions cultural institutions as active partners, not just recipients, in knowledge creation. It also sets out some brief implications for universities, cultural institutions and policy makers.

Importance of collaborations between universities and cultural institutions

Cultural institutions — such as museums, libraries, archives, collections, theatres, heritage sites — are vital hubs of knowledge preservation, creation and diffusion. They preserve and share culture and heritage while engaging diverse audiences. Their public mission closely aligns with universities’ educational and civic roles, providing rich opportunities for collaboration (Comunian & Faggian, 2014)[1]. By combining expertise and resources, universities and cultural institutions can turn academic research into benefits for society (Wilson et al., 2021[2]; Rossi et al., 2025[3]). This aligns with the ‘research impact’ agenda, according to which universities are increasingly expected to show that their work produces value beyond academia – generating impacts that are economic, cultural, social, environmental, political, and so on.

However, most of the evidence collected about research impact still focuses on collaborations around science and technology, where outcomes are easier to measure (Hessels & Van Lente, 2008)[4]. We still do not have a large amount of evidence about how universities and cultural institutions work together to produce and share knowledge, and what kinds of impact they achieve.

Evidence of collaborations between universities and cultural institutions

Using data from the REF 2021 Impact Case Studies database[5], our work aims to fill this gap by investigating collaborations between universities and cultural institutions, particularly trying to identify which collaborations have the most transformative impact.

The study draws on 6,361 REF 2021 impact case studies, focusing on 3,018 that involved formal partners. Among these, 286 cases included a cultural institution. Each case provided information about the type of institution, its partners, research area, and the kind of impact achieved—whether cultural, economic, environmental, social, political, legal or technological.

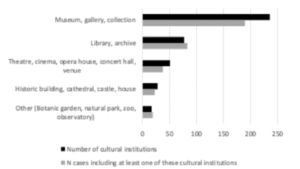

Figure 1. Cultural institutions involved as formal partners in REF 2021 impact case studies

Collaborations involving cultural institutions were typically smaller, more diverse, and more likely to have received external funding (but from a lower number of external funders) than collaborations that did not involve cultural institutions. The former focused less on traditional academic publication outcomes and more on creative knowledge, such as performances, exhibitions, or digital archives.

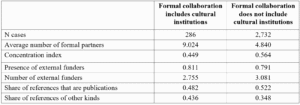

Table 1. Comparison between formal collaborations with and without cultural institutions

Different types of collaborations between universities and cultural institutions

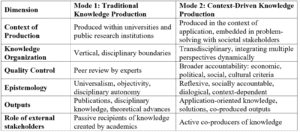

In order to identify patterns and distinguish between different types of collaborations, we build on ideas proposed by Gibbons et al. (1994)[6], to identify two main ways knowledge is produced:

- Mode 1 – Traditional academic research within universities. This tends to focuses on disciplinary expertise, peer review, and theoretical work, but usually involves limited interaction with outside partners. This approach strengthens specialist knowledge but can be detached from real-world needs.

- Mode 2 – Collaborative, problem-focused research. This tends to bring together universities, industry, government, and community partners to co-create knowledge that addresses practical issues. It values diverse perspectives and produces more socially relevant results.

Table 2. Comparison between Mode 1 and Mode 2 knowledge production

Knowledge dynamics and relationships

Mode 1 knowledge production processes are more likely to result in cumulative knowledge dynamics, that is, in the production of new knowledge that is close to and building upon the already similar knowledge bases of the participants (who are mainly academics, with external stakeholders playing the role of knowledge recipients). Therefore, we expect Mode 1 knowledge production processes to generate impacts on areas of knowledge that are closely related to the knowledge base of the collaborators. Additionally, in Mode 1 knowledge production, research teams are more homogeneous and hail from similar disciplinary and institutional backgrounds. In these contexts, bonding forms of social capital play a central role by reinforcing trust, stability, and shared interpretive frameworks that sustain incremental learning and path-dependent knowledge cumulation (Coleman, 1988)[7]. Therefore, we expect Mode 1 knowledge production processes to generate impact to specific social groups closely connected with the participants in the process.

Mode 2 knowledge production processes are more likely to result in combinatorial knowledge dynamics, that is, in the production of new knowledge that integrates the already quite different knowledge bases of the participants, and which can be quite far from the initial knowledge bases that the participants possessed. Therefore, we expect Mode 2 knowledge production processes to generate impacts on areas of knowledge that are not closely related to the knowledge base of the collaborators. Additionally, in Mode 2 knowledge production actors span organisational, institutional, and sectoral divides. To bridge these interfaces and build a common knowledge base, actors must actively invest in establishing mutual understanding. In terms of impact, we expect Mode 2 knowledge production processes to generate impact to broader social groups not closely connected with the participants in the process.

What drives transformative collaborations

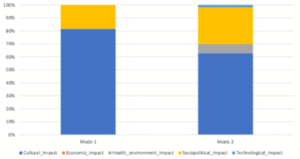

We find that cultural impact is by far the most common outcome. Museums, galleries, and heritage sites lead in this area, while science-based cultural institutions like zoos, observatories and botanical gardens tend to contribute more to environmental and global impacts. Smaller, focused research teams often achieve deeper cultural engagement, while larger teams tend to spread their impact across sectors.

We also find that collaborations can be broadly classify into a Mode 1 vs Mode 2 pattern:

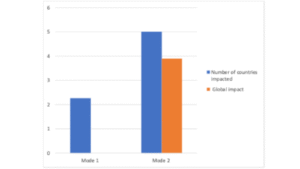

- Mode 1 Collaborations – Small, focused collaborations between academics and cultural institutions, mostly in the arts and humanities. They rely on traditional research methods and, as we expected, produce strong cultural outcomes with local reach.

- Mode 2 Collaborations – Larger, more diverse collaborations that also include universities, charities, and community groups. They are more experimental and practice-based, and, as we expected, they generate wider social, technological, or environmental impacts, often internationally. They are more likely to address contemporary Grand Challenges such as climate change, health, technology for social good, and placemaking.

Together, these modes form a balanced ecosystem: Mode 1 deepens cultural and disciplinary expertise, while Mode 2 drives broader societal change.

Figure 2. Types of impact of Mode 1 and Mode 2 collaborations

Figure 3. Geographical span of impact of Mode 1 and Mode 2 collaborations

Contribution of the research

The study contributes to understanding how universities and cultural institutions co-create knowledge by:

- Expanding existing research models (Mode 1 and Mode 2) to include the cultural sector.

- Showing how different forms of collaboration influence the type and reach of impact.

- Demonstrating the importance of trust and relationships—both within and across sectors—in shaping outcomes.

- Positioning cultural institutions as active partners, not just recipients, in knowledge creation and public engagement.

Policy and implications

Here we set out just a snapshot of potential recommendations for universities, cultural institutions and policy-makers and funders.

For universities, collaborations with cultural institutions strengthens the research base, augments the public value of arts and humanities research and helps build stronger community and place-based links. They can also play a key role in supporting grand challenges in areas including health, education, climate, place and technology for social good.

Developing collaborations takes time and capacity and that needs to be considered as part of the enabling process for academic and professional staff to pursue and support partnerships with Cultural Institutions, both large and smaller-scale.

Some universities work with CI partners and other actors such as local authorities to help shape Areas of Research Interest and other emerging challenge areas for the CIs. Universities who are embarking on work of this kind could consider developing such models as well as making investment in dedicated staff to further catalyse cultural activities and partnerships.

For cultural institutions, the findings highlight the value of working with university partners as a vital source of opportunities to engage in knowledge co-creation, innovation, and societal problem-solving. They also highlight the potential for sharing intelligence around the benefits of research partnerships through CI networks and sector specific press to encourage better awareness of collaborative opportunities and impacts.

Another key benefit of working with research is that it can also support disruptive thinking, encourage new modes of thinking and support change and innovation missions.

However, as is the case with university partners, there can be considerable resource and capacity implications that need to be taken into consideration when planning for research collaborations.

For policymakers and funders, the study suggests that current evaluation systems—like the Research Excellence Framework—should better recognise and reward diverse modes of knowledge production, cultural impact and community-level impacts, not just global or economic ones. Diversifying funding streams to support more context-driven research and to enable a wider range of experts to be engaged in both crafting and benefiting from funding bids should also be considered. These findings also have implications for the Knowledge Exchange Framework, as the move towards the growth agenda intensifies.

Conclusion

Collaborations between universities and cultural institutions represent a powerful but often overlooked way of creating a diversity of public and societal benefits. Mode 1 collaborations nurture cultural and disciplinary depth, while Mode 2 collaborations extend research into wider social and environmental arenas. Both are essential for universities seeking to combine academic excellence with civic purpose and emerging areas of concern, including social innovation. By explaining how different forms of collaboration produce different kinds of impact, this study helps universities, policymakers, and cultural institutions work together more effectively to maximise research’s contribution to society.

(If you are interested in reading more about research collaboration and transformative impacts in cultural institutions, you can read our sister blog that captures further perspectives from the following contributors: Sarah Campbell (University of Exeter), Ailsa (National Galleries of Scotland, Joanna Norman (V&A) and Evelyn Wilson (NCACE).

__________

[1] Comunian, R., & Faggian, A. (2014). Creative graduates and creative cities: exploring the geography of creative education in the UK. International journal of cultural and creative industries, 1(2), 19-34.

[2] Wilson, E., Hopkins, E., & Rossi, F. (2021). Collaborating with Higher Education Institutions: Findings from NCACE Survey with Arts Professional. Available at: https://ncace.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Wilson-Hopkins-Rossi-Collaborating-with-Higher-Education-Institutions-1.pdf

[3] Rossi, F., Baines, N., & Wilson, E. (2025). Generating societal impact from collaborations between universities and arts and culture organisations (ACOs): Evidence from a survey of arts and culture professionals in the UK. Technovation, 140, 103158.

[4] Hessels, L. K., & Van Lente, H. (2008). Re-thinking new knowledge production: A literature review and a research agenda. Research Policy, 37(4), 740-760.

[5] https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/ukgwa/20180903113600/http:/impact.ref.ac.uk/CaseStudies/

[6] Gibbons, M., Limoges, C., Nowotny, H., Schwartzman, S., Scott, P., & Trow, M. (1994). The new production of knowledge: The dynamics of science and research in contemporary societies. London: Sage.

[7] Coleman, J. S. (1988). Social capital in the creation of human capital. American journal of sociology, 94, S95-S120.