The following piece was the closing reflection presented by Roger Robinson (Poet, Writer, Performer) at our recent Culture, Collaboration and Knowledge Exchange: Technology for Social Good event in June

On Black British Grief and Social Media

Whether it's the British Nigerian communities' use of WhatsApp to share local cultural events and maintain a close-knit sense of community and extended family, or the Black British community in solidarity with the murder of George Floyd protests with the hashtag #BlackLivesMatter, or the use of subreddits to share information to ease the immigrant process into England, I have always been interested in the specific ways that diasporic people intuitively use social media in varied ways compared with other communities.

One specific case that caught my interest during Covid was the grieving ceremonies held for MC Ty spread across several platforms on social media. The content could be read across the various platforms to create a detailed and personal narrative of collective grief that seemed novel to me within the Black British traditions of grief and may be the start of a different way to approach grieving by adapting social media to the social and emotional need of a community.

Ben Chijioke, better known as MC Ty, was a hip hop MC who was never famous—at least not mainstream famous. The closest he had ever come to mainstream fame was being shortlisted for the Mercury Music Prize; at one point, he was widely tipped with an outsider's chance. MC Ty was, though, an artist’s artist, one who bucked many of the prevailing stereotypes of hip hop and leaned into craft, developing fans and making himself very accessible on social media where he was happy to debate and have conversations with just about anyone. On any given day, if you were walking through Brixton, you would see the tall, broad, and bespectacled Ty walking down the street, and he’d always have time for a quick and often witty and amazing conversation. I thought he was like that with me, but as I’d come to find out, he was like that with absolutely everyone he knew and met—and he knew a lot of people.

During the early part of COVID-19, Ty was hospitalised and, after a week, was released. Many breathed a sigh of relief, only to hear that he'd been re-hospitalised a week later, followed by numerous phone calls asking me if I’d heard that MC Ty had died.

From here on in, I will leave out my own personal feelings of grief to concentrate on the collective grief of a mourning community and how it centred on social media. This collective mourning was novel in that I had not seen the likes of it before, and it could be a template, if not a jumping off point for other diasporic and global majority peoples to assist each other in the mourning process.

So I mention the term curious in the title because I was curious as to how this particular form of social media grieving sprung up at least to the level in which I could clearly observe its constituent clusters.

Now, it could be said that a combination of world events and personal circumstances shaped how Ty was grieved in such a novel way. First, he was very active with his own artistic content on social media. Second, a lot of his artistic community fans from across the country were used to communicating with him on social media. Third, we were just entering a world of Zoom calls, separation, and isolation due to Covid imposed rules from the government, so social media took on added importance. Fourth, Ty was an artist with a lot of interaction with audiences and recorded shows of performance and interviews that people could repost to create a shared. Whatever the social circumstances that occurred around his death, what emerged was a social media-centred protocol to help with a community's collective grief.

The first indication of a Black British collective grief was on Twitter, where many disparate parts of the Black British artistic and media community converged and shared tributes, pictures, and memories, giving him his social media flowers, so to speak. The news on Black British Twitter networks travelled quickly due to retweets and quickly syphoned up to national and international media. The Sun, The Guardian, and The Independent published tributes to him on the day of his death announcement, and during the week, other major media outlets like The New York Times and Huffington Post covered Ty's death. Most major media outlets emphasised that he was a talent gone too soon, a victim of the coronavirus, and that his death was indicative of the broader impact of the virus. Next came a wave of tributes from media celebs like DJ Charlie Sloth, members of De La Soul, Roots Manuva, and others, who spoke about their respect for his artistry and friendship. But online, a particularly intense form of grieving began to develop that you could connect to if you were an extended part of his community:

On Instagram Live, there were a series of tributes where Ty’s music would be played, and intensely personal stories about his interactions with people were shared. Viewers were invited to comment and ask questions, celebrating Ty’s life and helping the community heal. (sidenote these Instagram Lives, called "Pass The Torch," evolved into a live series showcasing new young rappers that still continues). The combination of stories, music, and onlookers' live comments created a sense of both mourning, tribute, and epiphany.

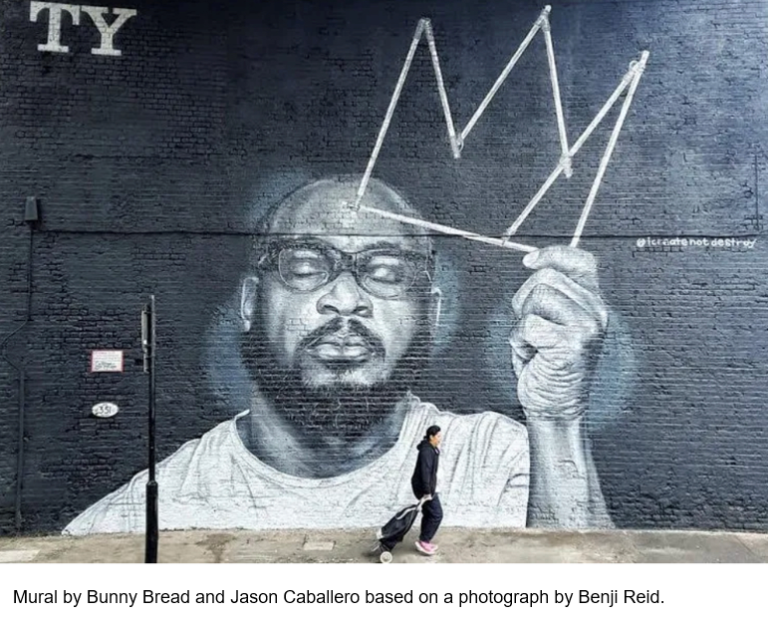

In Brixton, Ty’s hometown, two giant murals were created by artists close to Ty, with their creation processes being shared online. Besides being beautiful, emotional paintings that captured something special of Ty’s personality, the murals became sites of pilgrimage when people were allowed out of their houses. Visitors would take pictures of themselves there and share them online, sharing their memories and grief with a wider community and encouraging others to make the pilgrimage to the murals.

Realising the overwhelming outpouring of grief on social media and the international and local restrictions of movement due to COVID-19, Ty’s mother decided to have his funeral live-streamed on YouTube. There were moving eulogies delivered by his sister and his friend Breis. I talked to people from LA to New York who connected to the funeral rites online to mourn their loss.

The swell of online tributes took another turn. The next phase was the sharing of Ty’s personal private interactions on very public social media platforms. How he stepped in as a birthing partner for a pregnant mother to be, how many children he was godfather too, how he helped young men to budget and thrift for clothes, how many people he was their unofficial babysitter, how he mentored and developed many younger artists for decades, how many people he gave great life advice to. What emerged was a man who was not only connected to a bigger community but also embedded in touching and helpful ways within that community.

On Facebook, clips of Ty’s performances were being constantly shared. Performances ranging from dark dingy clubs to the gigantic well lit stage of the Southbank Centre with no lag in energy of his effort to really connect with audiences whatever the context. Ty was a skilled, professional, and engaging performer, so the juxtaposition of seeing him so full of life and knowing that he was now gone added another dimension to the grieving process—not only mourning Ty but also grieving an era in Black British hip hop before it evolved into the genre of grime.

What emerged with the collage of live, recorded and recorded testimonies was an emotionally detailed montage of his life centralised on social media with access to anyone who needed to grieve.

Tys death for the black British community became a nexus of grief due to the restrictions and ravages of Covid. His death allowed people to grieve their separation from their community , the Covid death of other people in that community, His death allowed people to grieve their lives as it existed before Covid which at that point seemed like it would never return.

The collective grieving process for MC Ty on social media serves as a poignant example of how digital platforms can facilitate a sense of community and shared mourning, especially in times of global crisis. It illustrates how social media can be adapted to the emotional and social needs of specific communities. The integration of personal stories, tributes, live interactions, and artistic expressions across various social media platforms created a rich tapestry of collective memory and support. This novel approach to grieving reflects the adaptability and resilience of diasporic communities, suggesting new ways to honour and remember loved ones in an increasingly digital world. Ty's legacy, amplified through these online ceremonies, continues to resonate, illustrating the enduring power of social media in shaping communal experiences of loss and remembrance is a very good use of social media.