Considering practice-based-research through anecdotal experiences across academia, museums and archival practices

While doing research for my PhD thesis at the Centre for Dance Research (C-DaRE) at Coventry University in 2019 I was in discussion with my then Director of Studies, Dr Natalie Garrett Brown who suggested I use the term ‘practice-informed-research’ rather than the more common ‘practice-based-research’. This differentiation of wording struck me as important in that my approach to research was not one in which I drew directly from current, in progress, creative practices but, rather, from a reflection on past artistic works and processes. This meant that the knowledge transfer between practice and research or, the ‘doing’ of the practice and the writing about it, was informing rather than providing a basis for which to articulate.

I am frequently in positions where I must explain practice-informed-research to both practitioners and researchers. What feels important to emphasise is the role that embodied or body-based knowledge plays in informing, collaborating with and intervening in verbal and written forms of expression and knowledge production. The divide between practice and research is still influenced by associations with ‘practice’ as a creative act, a movement, a doing with the body whereas writing a space of thinking and articulation of the practice.

More recently a staff member working in a university continued to explain to me that she was not a researcher and found writing an academic research bid challenging. I re-iterated that I approach research as a practitioner and that performative forms of writing and academic speak may not be that different.

Emily Pringle, former Head of Research at Tate, once asked me as part of my Associate Research role at Tate what research has meant to my practice as an artist. Or, in other words, do I feel I am ‘doing research’ when I am engaged in my practice. I explained that research has always been a part of my creative practice. As a choreographer I worked with dramaturge, Guy Cools, trained as a writer to conduct research on themes relevant to the project. For example, we read Barthes when I was creating a choreographic work about the gaze and visuality in dance to underpin the ideas in the work with theoretical enquiries and as a way to communicate the theme to the other dancers.

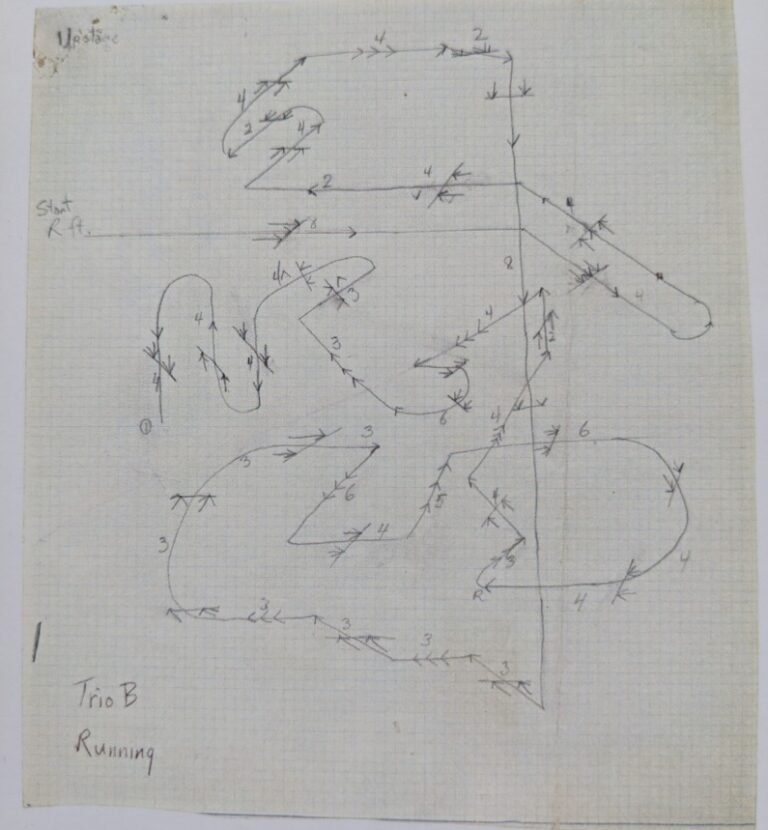

Yvonne Rainer is well known for writing about her own work in her book Work 1961–73 a conceptually rigorous and reflective piece on her practice in the way she wants it to be understood. The writing is a direct reflection of her choreographic methods, including drawings, sketches and notes taken as part of the dance making process. She is one of few artists to take on such an extensive overview of their own work. The book does not aim to fit within an academic context of writing and, yet its rigour, complexities and intelligence coming through her articulation of practice and it teaches us something about expanding out definitions of practice-informed or practice-based research.

How might the practitioner, in my case, of dance and choreographic practices bring new approaches to writing and practice-based methodologies of academic writing? An example that comes to mind is the work of Cori Olinghouse - whose archival research of performance or what she calls ‘an embodied and living archives framework’ - where she adopts the language of dance improvisation (term such as ‘looping’) to address the archive. She is interested in circumventing, intervening in and questioning historical traditions of academic rhetoric within archival research and practices. She does this through bringing in the language of dance – not necessarily only the physical language, but the words, phrases and invented language dance artists use when creating work, when practicing their craft.

I am currently completing evaluation work with Museum of Colour as part of People’s Palace Project through Queen Mary University and leaning on ways to write up an evaluation that includes practice-led and creative methods, from the knowledge I hold in my body and the words I use to engage an embodied approach to research and evaluation. I am also interested in engaging embodied practices and ways of knowing and understanding complexities in our evolving worlds, with technological developments, through my Affiliate Researcher role at the Minderoo Centre for Technology and Democracy (MCTD) within the Centre for Research in the Arts, Social Science and Humanities (CRASSH) at the University of Cambridge. What does a body do here? What embodied pedagogies, practices and ways of knowing are useful, productive, challenging and playfully provocative here?

As I move forward and continue to engage a practice-informed-research model through contexts of dance in the museum, archiving, collecting and conserving dance and new evolving technologies, I look to create bridges across these areas and to continue to insist on practice - both physical and linguistic – that is derived from dance and choreographic knowing in order to contribute to the changing landscapes across the arts and HE sector in the UK and beyond.

_______________________________

Sara Wookey’s transdisciplinary research across architecture, design, choreography, urban studies and museology is informed by her 30 years as an internationally recognised dance practitioner. Her research is informed by her work with the late urbanist Edward Soja and the theories of ‘felt space’. Sara asks pressing questions about the nature of human interaction that find articulation through public sector spaces such as theatres, museum spaces, health care sites and academia. Her current concerns are in how expanded choreography can help to change the human imagination of relationships between bodies and space in ways that can be more inclusive and sustainable and practice-based methods of archiving, documenting, collecting and conserving the performing arts. She is one of eight dance artists and custodians to the repertoire work of the iconic choreographer Yvonne Rainer. Affiliates include Tate Modern, Art Science Museum Singapore, Van Abbemuseum, Cambridge University Museums. She is an Associate Researcher at the University of New South Wales on the project Precarious Movements: Choreography & the Museum and is an Affiliate Researcher at the Minderoo Centre for Technology and Democracy. She has been published by Valiz Press, Routledge and Art Review and has an upcoming book review in Dance Chronicle. More information can be found at: www.sarawookey.com

Image credit:

Score for "Trio B, Running" from The Mind is a Muscle (1966-1968), 1968

Graphite and ink on paper

The Getty Research Institute, 2006